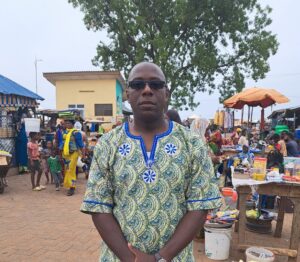

Dr. Chandler at the University of Ghana’s Modern Language Department.

My sabbatical plans, as laid out to the committee responsible for reviewing and approving faculty sabbaticals at Oglethorpe, were originally centered exclusively on the Andean nation of Ecuador, where my goal was to spend most of my semester-long leave in South America researching and becoming better acquainted with the vibrant but oft-ignored culture of Ecuador’s African-descended population.

However, in the midst of the Fall 2022 planning for my Ecuador travels, I received some wonderful and wholly unexpected news: I was extended an invitation by the University of Ghana to make the transatlantic journey to Africa to set foot once again on their beautiful Legon campus in the capital, Accra, as a visiting scholar of Spanish. Accepting the invite would allow me to return to West Africa and work with the talented students and faculty in the University’s Modern Languages Department—as I had done during a previous sabbatical some seven years earlier.

The memories of my 2016 “Ghanaian Sabbatical” and the life-changing impact of the experience were still fresh in my mind, and in fact, will remain forever near and dear to my heart for so many reasons, both professional and personal.

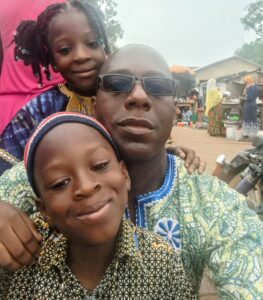

Dr. Chandler with family in Africa.

As I became excited about the prospect of traveling to Ghana and immersing myself once again in the vibrant and intoxicating culture of West Africa, a sense of disquiet rebelled against the sentiments of excitement and euphoria. Would I have to make a tough choice between my original Ecuador plans and the new Ghana plans that were now on the table? Traveling to one destination and not the other would surely take away from what could be achieved during a sabbatical that only comes around once every seven years or so, but traveling to both destinations situated on two different continents in two different corners of the planet would be ambitious, not to mention challenging due to the constraints of time, resources, and family obligations. In the end, I convinced myself that going the more ambitious route was doable despite the challenges. My dual-destination sabbatical split between Ecuador and Ghana was a feat managed through careful planning, some financial belt tightening, and a lot of support from my family, who, we decided, would accompany me to Ghana, providing my wife and children (who were all born in Ghana) the opportunity to return to their country of birth and to become reacquainted with the culture(s) and language(s) of their African heritage, a decision that would be especially impactful for our twin children, who were only nine-months old when they left Ghana for the United States.

To accommodate my project in Ghana that would be much longer in duration, my Ecuador plans would have to be modified and abbreviated. I spent several weeks in December in Ecuador’s Valle del Chota, a stunningly beautiful valley running along the Andes mountain range covering the northern provinces of Imbabura and Carchi just south of the border with Colombia.

The Valle del Chota in northern Ecuador.

As one of the country’s most important centers of Afro-Ecuadorian culture, the Valle del Chota contains dozens of small villages and towns populated largely by black Ecuadorians who have preserved their unique culture through oral traditions, spiritual practices, and culinary techniques inherited from their African ancestors who were brought to Ecuador as enslaved peoples as early as the mid-sixteenth century. For someone who has spent significant time traveling throughout the African continent, it is fascinating to see Afro-Ecuadorian women still carrying goods on the tops of their heads as continues to be the practice today throughout much of Africa.

A random snapshot scene from any one of the black villages of the Valle del Chota could easily be mistaken for a village in Ghana or in Senegal, an observation that was made recently at a seminar that I gave at the University of Ghana entitled, “Afro-Ecuador: Black Culture and Community in the Andean Realm,” featuring many visuals from the Valle del Chota.

An Afro-Ecuadorian woman carrying goods on her head.

In my seminar talk, I highlighted the unmistakable transatlantic links that connect Latin America with Africa in art, music, spirituality, and culture as a whole. Relevantly, I also talked at length in the seminar about an alarming migratory phenomenon whereby Ghanaians (and by extension, West Africans) are increasingly taking advantage of the less-stringent immigration policies of some South American countries as a springboard for attempting ultimately to reach the United States or Canada via Latin-American migration caravans. Attempting is the operative word here because the journey is unbelievably difficult…and dangerous. And sadly, though no concrete statistics are available, it is known that some young Africans do not survive the trek or they manage to reach the U.S.-Mexico border deeply scarred by hunger, injury, sickness, and the unspeakable trauma that they experienced and/or witnessed over the period of up to several months that it can take to travel by multiple means of transportation—car, motorcycle, canoe, and foot—through the longest and probably most difficult stretch of the trek, the “dulce cintura de América” (the delicate waist of America), as Chilean poet, Pablo Neruda, described Central America in his iconic poem, “La United Fruit Co.”

Caldera: An Afro-Ecuadorian village in the Valle del Chota.

I know the story all too well from Ghanaian students that I taught in 2016 who have attempted it, from Ghanaian acquaintances and even in-laws who know of my connections to South America seeking my advice in order to chance it, and even from happenstance encounters in Ecuador with Ghanaians and other West Africans actually in the midst of their movements through the country en route to Colombia and other points north. Indeed, and I confess, the story is uncomfortably familiar to me: a young Ghanaian manages to secure a “tourist” visa to visit Brazil, for example. He flies from Ghana to Brazil, though enjoying a pleasant tourist experience in Rio or São Paolo and soon after returning to Africa is hardly his endgame. Once in Brazil, he wastes little time using a digital roadmap left by others before him and a sophisticated network of coyotes (illegal migration middlemen) spread throughout the hemisphere to begin hopping from country to country passing through cities, villages, and even rainforests and jungles—northbound—crossing countless informal borders, as many official borders, in Central American countries especially, are difficult for Africans to cross without the necessary documents and visas. Ecuador, being one of only five South American countries through which the Pan-American Highway, stretching from Alaska to Argentina’s Ushuaia, has in recent years, become an important gateway country for African migrants attempting the journey north. Interestingly, the Pan-American Highway in northern Ecuador traverses some of the black villages of the Valle del Chota. One of the largest of the Afro-Ecuadorian towns called El Juncal is also one of the two last black communities at the northern reaches of the Valle del Chota. El Juncal sits right on the Pan-American Highway and has become an important transportation hub for travelers wishing to reach and ultimately cross the border into Colombia, two hours further north. While most African migrants headed north through the Valle del Chota are already situated on a bus or some other form of transportation that they secured in Quito hours earlier, an occasional migrant making his way north in piecemeal segments has been known to stop over in El Juncal for a rest, for a meal, or in search of independent transport to the border. The African migrant passing through El Juncal might be shocked to find himself in a community of Afro-Ecuadorian residents, shopkeepers, and restaurant owners that look like him or relived that his presence is hardly shocking in this part of Ecuador, an area populated largely by people whose ancestors themselves migrated, albeit by force, from Africa centuries ago.

Dr. Chandler in Ecuador where the Pan-American Highway passes through El Juncal.

The black population of Ecuador constitutes a little over 7 percent of the country’s total population. In a country whose racial demographics tend to highlight its sizeable indigenous and mestizo (mixed race indigenous and Spanish heritage) composition, the demographic focus on Afro-Ecuadorians, throughout the history and even contemporary reality of Ecuador, has sometimes come at the expense of appropriately crediting the existence of blacks in the country internally, and externally, in non-Ecuadorians’ racial imagining of Ecuador. In other words, people who have never been to Ecuador tend not to think of black people when they imagine the people of Ecuador. It is fair noting that the same holds true in many people’s imagining of Latin America as a whole, where brown and indigenous are the default conceptual imagining, with African contributions not always calculating into people’s perceptions of Latin-American identity despite longstanding historical presence and contributions of Africans in the key struggles and movements of Latin America since the Colonial Era.

Afro-Ecuadorian culture is frequently relegated to the periphery of Ecuadorian society despite an undeniable physical and visible presence of African-descended people throughout Ecuador, not only in small town and villages like those of the Valle del Chota, but also in the larger urban centers of the country such as the capital, Quito, and the country’s most populous city, Guayaquil, for example. Nonetheless, Afro-Ecuadorians undeniably have exerted significant influence on the wider national culture in numerous arenas from art to cuisine, from sports to politics. One of the achievements of my Ecuador project was having become better acquainted with the network of black villages of the Valle del Chota and having spent time among Afro-Ecuadorians, learning firsthand about their history, their cultural and culinary artifacts, and their stated challenges and triumphs in contemporary Ecuadorian society. Ecuadorians in general are very hospitable and Afro-Ecuadorians are certainly no exception to this rule, a fact that contributed to me being warmly welcomed into the homes of Afro-Ecuadorians to observe the preparation of a local recipe like fréjol choteño (a bean preparation from the Valle del Chota) or to participate in a birthday celebration among friends.

Celebrating with an Afro-Ecuadorian family

The Spanish courses that I teach at Oglethorpe featuring Ecuador, such as my Hispanic Culture Through Cuisine course (SPN 203), will certainly benefit from future units that are more inclusive of the African contribution to the rich cultural and culinary traditions of Ecuador and that in the future must necessarily touch on the pressing issue of West African migration to and through Ecuador, a topic that over the past several months has come to occupy an even greater space in my consciousness and awareness as the result of a sabbatical travel experience bookended between Ecuador and West Africa. My brief sabbatical stay in South America, in addition, inspired a desire to design a future J-Term course focused on Ecuador that will have a travel component to it allowing Oglethorpe students to experience the Valle del Chota, as well as other extraordinary sites in Ecuador, for themselves.

Mere days after departing Ecuador, I was on another flight, this time bound for Ghana. As my sabbatical experience on two continents unfolded, many links between Ecuador and Ghana came even more clearly into view. A discernible, but elusive familiarity between the two countries has remained with me since my arrival at Accra’s Kotoka International Airport on the first day of the New Year of 2023. Is it something simple and benign like the irresistible Pacari (Ecuador) and Kingsbite (Ghana) chocolate products that the two global cocoa giants produce and that, at the same time, satisfy my sweet-tooth craving in remote spaces where no Krispy Kreme Doughnuts are to be found? Or is it the colorful cinderblock-based houses equipped with plastic black polytanks for water storage that form the foundation of Ecuadorian and Ghanaian dwellings alike, and that I see at every turn, temporarily crisscrossing my wires of placement, especially if startled out of slumber during a long road trip through the African or Andean countryside? Or, maybe it’s something more profound like the beautiful features in the faces of the Afro-Ecuadorian people with whom I had spent time weeks prior; regal, Nubian features that leave little doubt that distant African ancestors survived the Middle Passage and made their way to Ecuador centuries ago, struggling, thriving, and attempting to make sense of and build a new reality in a foreign, Spanish-speaking land that takes its name from its location on the American equator.

Typical busy market scene in Ghana.

Undoubtedly, coming back to Ghana had all the trapping of a homecoming, a return to a familiar space with familiar sights, sounds, sensations, and people, especially from the University of Ghana community—colleagues and even a few students from my 2016 experience. But my most recent arrival in Ghana just days after my departure from Ecuador evoked interestingly curious sentiments of perplexity that continued to surface from time to time throughout my time in Africa. To supply an example, I left Ecuador, a place where in some instances, especially in marketplaces, banks, and business offices, I was required to mask up for entry as continued precaution against Covid-19…or be denied entry into those places. Days later, I arrive in Ghana, where aside from the occasional voluntary mask wearer that you come across, for the most part, masking is a thing of the past—at least for the time being one should stress. The fascinating shock to the psyche is to be in a Latin American country today, where entering a sparsely populated village supermarket requires masking at the firm behest of the security guard standing at the store’s entrance, and on the flipside, to be in an African country a few days later, where entering even the most heavily populated markets of the capital, like Accra’s Madina or Nima markets, with hundreds of people going about their trading and transactions unmasked and in close proximity to one another, making you ponder on, not only the arbitrary nature of the world’s response to and management of the Covid crisis, but on your own precautionary actions and choices depending on where you find yourself in the world at a given moment.

There’s a popular African proverb that goes something like this: “You can’t easily wash the dust of Africa off your feet.” As I a little too rapidly approach the tail end of my second Ghanaian sabbatical in the past seven years, I realize how strongly the reality of that proverb rings true. In 2016, I had the deep honor of being invited to the University of Ghana as a visiting scholar for the first time. While the invitation was not actually my first visit to Ghana, living in Africa and engaging daily in scholarly activities with West African students and colleagues impacted me indelibly. I do not exaggerate when I say that the experience was life changing for a number of different reasons. As a black American, descendant of enslaved African people, my semester-long stay in Ghana in 2016 afforded me extended time (and apropos space on the Continent itself) to nurse many observations, reflections, and personal reconciliations on what it means to be an African descendant living in Africa, and in a wider sense, what it means to be a descendant of Africans living quotidianly in other parts of world as, let’s say, a Spanish professor in Atlanta, as a study abroad leader in Barcelona or Cape Town, or as an ordinary tourist making his way through Casablanca or Medellín. I recorded some of these reflections in my project, Gazing the Black Star: An African American Contemplates Ghana. A follow up to my 2016 Ghanaian experience would necessarily explore a perspective that was circumstantially missing from my earlier Ghana gazings. I was not a parent in 2016, and in fact, parenthood was not remotely on my radar at that time, and yet, seven years later, remarkably, I find myself the father of two amazing children, fraternal twins who were born in Ghana, and whose very lives are the quintessential and literal definition of “African-American.” After all, one parent is an African, and the other, an American. Since their birth, I have witnessed, to my amazement, the twins straddle and negotiate the complex boundary line between two cultures with extraordinary finesse, delicateness, and sophistication. Through their birth, and through my marriage union with their Ghanaian mother, I sense that I have accomplished something quite meaningful: I have sowed strong kinship seeds deep in the soil of an African culture in which kinship ties are supremely important. And in so doing, I have achieved an endeavor that many blacks scattered throughout the diaspora desire and deeply crave. I have returned to Africa, but not in a romanticized, abstract, or distant sense of return, but rather, as a tangible restoration of a vital part of my identity vicariously through my African-born children, a rearrangement, as it were, of broken pieces. Seeing them adapt and adjust to life in Ghana alongside me during my sabbatical—bonding with distant African relatives and newly-made African schoolmates, eating local dishes like banku and waakye expertly with their hands, picking up daily, new words and phrases of Twi, Ghana’s most important ethnic language—has been deeply gratifying, experiences that will not too soon be forgotten by them, but above all, by me.

Dr. Chandler with twin children in Ghana.

In addition to the personal bounties associated with my sabbatical travels abroad, there have been, undoubtedly, many accompanying professional bounties as well. One of the most rewarding and intriguing aspects of my two sabbaticals in Africa is having had the opportunity to work closely with students from Ghana and from many other African countries (given the University of Ghana’s appeal and reputation continentally,) not only in the traditional classroom setting, but also in professional and academic mentorship opportunities outside of the classroom. The instructional experience in Ghana has been nothing short of amazing. I admit that I have probably learned far more from my students than they have from me. The University of Ghana, the oldest and largest public institution of higher learning in the country, has approximately 38,000 students! So, most of the instruction halls, including the ones I taught in, are intimidatingly huge. But my students quickly put me at ease with their warm welcomes, their smiling faces, and their overall courteous and deferential demeanor in their interactions. And despite the obvious tone of formality with which students approached and engaged me, they were also sufficiently relaxed to have fun and even give in to their youthful mischief from time to time. I have found that the regard and respect that African students have for their professors and for the pursuit of learning in general makes it easy to connect with them in ways that are meaningful and impactful.

Dr. Chandler with Ghanaian students and mentees.

This term at the University of Ghana, I taught two classes: one, a selected topics course that I designed focused on U.S. Latino/Latinx culture and literature, and the other, an Advanced Spanish Translation course. A strong and vibrant Spanish program at a Ghanaian university might seem out of place considering the fact that Ghana is a lone anglophone country surrounded by a sea of three French-speaking neighbors: Ivory Coast, Burkina Faso, and Togo. Ghana is also an ocean away from the Spanish-speaking Americas. And yet, the University of Ghana’s Spanish program is top notch and ever-growing, evidenced by the heavy enrollments in my two courses, not to mention the hundreds of Spanish student oral exams that I recently helped evaluate alongside a wonderful team of Spanish program colleagues, a diverse group of talented lecturers from Ghana, Cameroon, and even Spain.

The University of Ghana’s dedication to building and sustaining a strong Spanish program can certainly be attributed to its global vision and outlook, but also to the fact that there is one Spanish-speaking neighbor actually located on the African continent, a tiny nation in Central Africa called Equatorial Guinea, whose relatively recent prosperity attributed to revenue from its vast oil reserves, has spawned African interest in Spanish language and Hispanic culture throughout the continent. I was thrilled to work with students on individual thesis projects focused on Spanish-related topics such as Equatorial Guinea as well as aspects of Spanish language and translation. In addition, I directed group projects centered on various Latino/Latinx communities and their respective Latin American countries of origin. The group projects were especially stimulating, most notably in the salient connections that my students were making between Latino culture and their own culture, highlighting, for example, African cultural preservations identifiable in Latino practices today as well as analyzing the complex fusion between Latino and African identity among African-descendants in various Latin American societies. Indeed, my students’ research focus points dovetailed beautifully with my own, forming a full circle of intersectionality that begin with my arrival in Ecuador months prior. In closing, I will return to Oglethorpe renewed and enriched by my sabbatical journey to Ghana and Ecuador. The sites seen, the relationships forged, and the experiences that I enjoyed will not too soon be forgotten. My international sabbatical has been one of great meaning, purpose, and achievement.

Photo at top: Dr. Chandler with Spanish students at the University of Ghana.