Dr. Stephen Goodwin is a lecturer of German and Core Studies at Oglethorpe.

“The first time that I was in Bosnia just after the war I was arrested for taking pictures. At the end of the day, they let me go—in fact, they invited me out for a beer.

I was in Sarajevo taking pictures, and I tried to take a picture of this little boy. The sun was shining on his blondish hair, and he had a red shirt on—it was a really nice picture. But I just couldn’t get it in focus.

I didn’t even take the picture, but the police saw me with the camera. What I didn’t realize was that behind the boy was this police station that had a big hole blown in it from a mortar. And they thought I was taking a picture of the police station. So they hauled me off and interrogated me.

They wanted to take my film and wanted to know what else I had taken pictures of. And I said, things of the military on the streets, destroyed homes, children playing among shrapnel, people and their faces—and then of course, I took pictures of the famous bridge where Franz Ferdinand was assassinated. And then they just lit up—like, oh, do you like history? You know about that! I guess they were too used to people that didn’t know anything about their history. And that just brightened their eyes, and somehow, we became friends. And they let me go with my film, and I was very happy about that.

These were the times when Europe was really changing. The Berlin Wall was taken down in ’89. The political will was there to make big changes in the area. My wife and I went to former East Germany in 1990 and were probably the first Americans—though there’s no way to verify it—to live in Dresden since the Anglo-American bombing in 1945 that so devastated the city center, and the collapse of the socialist state.

Those were fantastically interesting times. There was a lot of optimism, because these people had been living in totalitarian states, and there was a kind of euphoria, people excited about the changes that were coming. But then the realities of higher expenses, higher rents, not as much government support—these things all changed their lives dramatically, and the euphoria turned to resentment and despair because the system that they were completely dependent on had collapsed, and they couldn’t any longer make ends meet.

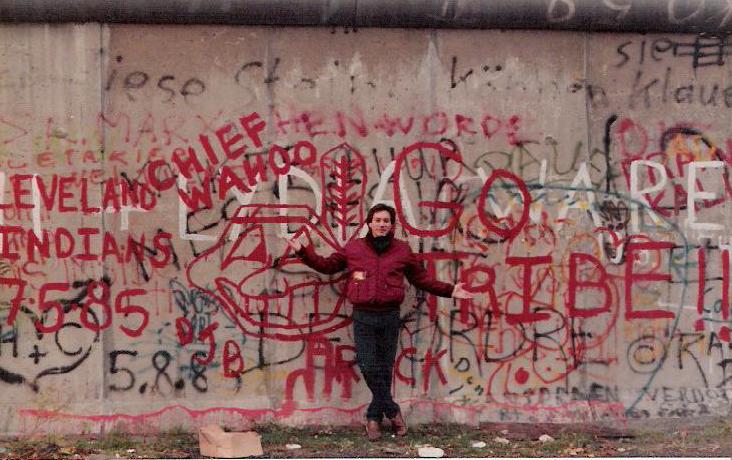

Dr. Goodwin at the Berlin Wall, 1985

In the Balkans, that is to say, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Kosovo, I was working with local groups that were engaged in support of refugees, to humanitarian aid causes, to microenterprise causes, anything that would help people get back on their feet. So, I was in the camps in Kosovo and Albania during that crisis.

The refugee situation wasn’t long, but it was intense, and some of the bigger news agencies—I won’t name them, but their initials are CNN—would stand outside and sort of breathlessly report on the situation, giving the impression that their presence was helping refugees. But being in the camps, and talking to the refugees, figuring out what they need; distributing things – like diapers, or baby food, baby formula, drinking water, food, provisional shelter – then the magnitude of the issue could be gauged and addressed with international relief. Other places we weren’t able to sleep because the whole night long you would hear refugees just streaming out of Kosovo into northern Albania.

And then there’s just the pure psyche of people, which is that they’re living under extreme circumstances with a lot of fear, a lot of trauma, and an incapacity to earn any sort of living. Everything that they had was ripped from them. Trying to address these fears, the hatred that they have… Well, you can get water and electricity running again, you can get the trams in Sarajevo running again; those structural things all need to happen, and they do, after a time. But how do you address the human aspects of fear, of angst, of hatred, of trauma? Those are the human sides, but honestly, the structural things are easier to fix; it’s difficult to explain to international people that a lot of the efforts, while necessary, were also fairly superficial, and that the same internal fears that started the conflict remain today.

In ’96, the Dayton Accord was signed, halting the fighting in Bosnia, and we moved from Poland to Budapest. My family was really young, in fact, my second daughter was born in Budapest. And going into a post-war zone was not a place for a young family. Infrastructure was completely devastated by a four-year war—no water, no heat, no electricity, food was hard to come by. Just really a bad situation.

Coordinating of humanitarian aid was the big effort initially, and then trying to improve self-sufficiency and sustainability. Peacebuilding was also a large focus, which means you must learn and confront the toxic national myths that led to war. But because I had a young family, my wife didn’t travel with me anymore. I was gone about 110 days a year. I didn’t travel much in the winter, because it’s too dark—and sometimes you could get stuck in Sarajevo for three weeks in a blizzard or fog.

But traveling that much was not healthy for the family, and I realized that my wife and two small children were able to get along without me. But there was something quite insidious about this, that I was sort of a father in absentia.

One time I was just coming back from Bosnia, so I drove from a long way away, and I was needing to fly to Berlin to meet with some people from a different team. And I did that on a regular basis, every six weeks or so. I got home on a Friday afternoon, and I needed to get up at 5:30 to catch my flight to Berlin from Budapest. And my daughter was excited to have me home, she’s still in her onesie, ready for bed. And she said, “You just got home, daddy—you’re going away tomorrow?” and I said, yeah, I have a short trip over the weekend, just two sleeps. And she says, “Don’t go, you just got home.” And I’d heard that before, and it sort of moved me, but you know—this was just what I did.

The next morning I went in before leaving, and kissed her, and accidentally woke her. Her eyes are half shut, and she says, “Daddy, are you leaving?” I say yeah, and she gets out, runs past me to the door, and throws her arms out—literally, in her onesie, blocking me from going out the door. And she says, “Don’t, daddy, don’t go, stay with me, play with me.” I picked her up, she’s like three and a half years old—and brought her back to bed.

And I never recovered from that moment. I shed a few tears, and I realized that this was not sustainable. I largely had accomplished what I felt I needed to do in this region, and was already turning over some responsibilities to others. And so I determined on that trip—you know, it’s an hour and a half to Berlin on a flight, you’ve got time to think—and I determined, it’s probably time to move on. Other people can do this now.

So I came back home to Budapest, and I cancelled the next meeting. But I was thinking, you know, should I go? I really should go. I didn’t go. They called me, said, hey, you signed up for this thing, where are you? And I said, I’m home with my daughter.

Dr. Goodwin speaking at the National UN Model meeting in Turkey.

I had been doing a lot of teaching anyway, and I was encouraged to do a PhD on some of the things I had been working on. I looked at a few schools in Britain and a couple in Germany, and I found the University of Edinburgh in Scotland to be just the perfect place.

It was a great experience, a wonderful place to bring up the family, and I was home every night, which was the nice thing. I could read my children stories, we could wrestle together on the floor of the living room; I was home, I was a father. And gradually those frequent flier points just went away, and I never looked back. It was absolutely the right decision, and we were all happier.

After I finished my PhD, the situation in Bosnia still was unsuitable to raise a family in, and there were opportunities that arose in Turkey. We went to Istanbul for what I thought would be a year or so for post-doctoral work…but once we got there, we really loved Istanbul. And there were opportunities for my kids, for my wife—it wasn’t a post-war situation. It was a much healthier family situation for us. And I did a year of post-doctoral work before finding a teaching position at a large private university in Turkey, where I taught for 11 years.

That was really the turning point. Turkey gave us opportunities that Bosnia couldn’t. And each step was more interesting. People ask me all the time, what was your favorite place—Germany, Poland? Bosnia? Turkey? You need purpose for every place. You need a purpose for being there. And if you’re misplaced, either in timing or in gifting, you might struggle with it for a while. And you need to move on.

In some ways I still feel like I’m a young man—I’m not a young man. But if you can embrace who you are at the age you are, the experiences you have and the people you’ve met, it makes the whole experience really worthwhile. So my time and place now is at Oglethorpe. And I love it. Good place. Good people. New adventures.”