Lidia Labrada ’23 is a junior double majoring in art history and Spanish.

“I was eight when I found out about the significance behind my legal status. The conversation started because of the standardized testing that starts in third grade. I remember I got my testing materials, and there was a ‘G’ for my middle initial. And I was confused—because I don’t have a middle name. For as long as I could remember, it was just Lidia Labrada. Turns out the G is for my middle name, Guadalupe. And if you know anything about Mexican culture, and Catholicism, you know about la Virgen de Guadalupe. She’s a saint in Mexico, and we very much love her. We have a day dedicated to her. So, my middle name is after her. But that started the conversation: ‘why do I have a middle name that I don’t recognize? What’s the cultural significance of it?’

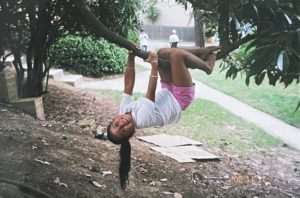

A young Lidia swinging in the trees near her childhood home on Buford Highway

I was also beginning to question over a little scar on my arm. When you come from a different country to the U.S., you get this little vaccination scar. As a kid, I never really paid a lot of attention to it, but one day I started asking questions: ‘what’s going on here? Why don’t the other kids at school have it? ‘

Around this time, as well, was the economic recession. And everyone was impacted by it, including my dad. I didn’t necessarily know what was going on, but I remember everyone always being pretty grouchy. Also at this point, these new laws were coming in about people who were undocumented in Georgia. I think at the time it was ‘HB ochenta y siete’. House Bill 87. It targeted a lot of undocumented immigrants who were driving without a license, or stuff like that. So with the laws, and the recession—everyone’s running around with their heads chopped off. It was a really crazy time.

I remember we were having dinner. And we always have something playing, in my family, so I could hear the news in the background. And I’m sitting there, and my dad’s like: ‘you do realize that you can’t tell people you’re not from here.’ And I was like, what do you mean—I thought I was from here. And he said, no, you’re not from here. Have you ever checked your arm?

That’s when I found out the meaning behind the scar. And during that dinner, my parents just decided to pull all the cards out. Explaining this and that. If police ever show up to your school and ask you where you live, do not say anything. You can’t say anything, you can’t say your mom and dad aren’t from here—basically, if you can avoid the situation, don’t talk. My dad said that saying something to the wrong person, even if it’s your teacher—you don’t realize the impact it could have.

During this time, a movie came out: Under the Same Moon. Abajo la Misma Luna. And it was very fitting. That’s when I realized what can happen if you have your legal status out there. Especially if you’re working. And from then on—even to this day, going to class, my first thought is always: if I’m not texting my parents right now, how do I know if they’re okay? My dad’s at work—did he make it there okay? How do I know if he’s going to come back home? It’s all those questions and realities that you realize coming from that one moment when you find out. Knowing that you’re not from here, and you’re not safe.

Lidia’a vaccination scar, located on her upper arm

From that time on, I just remember being super quiet. And not wanting to talk about certain countries. And even to this day, when people ask me where I’m from, I always get confused. Are they asking me where I was born, or where I was raised? It’s a weird question. I was born in Guanajuato, Mexico, but I was raised here since I was two months old. I don’t want to say I’m from Atlanta. I’m not, I wasn’t born here—my arm can tell you that. I like to distinguish this difference with the phrase ‘no soy de aquí, ni de allá.’ ‘I’m not from here, nor from there.’ Growing up I never knew where I fell, and I still don’t, so I often find comfort in this phrase.

That scar is just a really big reminder of things. And it was worse in high school, because I would actually use a Band-Aid to cover it up. That’s when Trump came into office, and I don’t want to invoke politics into this, but just in general that period of time was really bad. If I could cover any kind of identity at the time, that scar was it. Now it’s more of a sense of pride, but back then I used to cover it up. I didn’t want anyone to know about it.

The magnolia on my arm comes from a place of nostalgia. It reminds me of my childhood on Buford Highway, and connects me to that time when I was able to climb the trees, and pick the buds, and smell the aroma of the flowers, without having to think about my legal status. It represents a young, wild and carefree Lidia before the pressure of having to know about being an immigrant, and what it really stands for – what being undocumented meant at the time. It takes me back to that happy time. And it reminds me of change – everyone blooms into their own person. Everyone grows, and the magnolia helps me feel less alone in that.

This is going to sound really cheesy, but it’s definitely when I started coming to college here that my identity became a source of pride. I know about the policies, and why I can’t attend college like a regular student. I’m not allowed to go to public institutions, and if I do, I have to pay out of state tuition—and that’s a lot on me and my family. It wasn’t until I got into Oglethorpe that I met people that honestly did not care about any of that. And there are a few of them who have the same scar. It’s become a little ongoing joke that my friends and I have the same mark, but I love it so much. And I’m finally able to do all the things I dreamed of that I didn’t get to do in high school. So now, yeah, I walk around with my little scar all out. I haven’t thought about covering it up in forever and a half. Which is a relief.

Lidia at her kindergarten graduation

Last year, I realized that I don’t want to keep carrying it anymore. The image of, oh, it’s that undocumented girl at Oglethorpe. I don’t want to keep carrying it. I’m tired of it. I’m tired of fighting a fight that for me, personally, is just useless. It’s weird to get asked political questions, or questions about my legal status, because I can’t control anything. I had a project last year that required me to define ‘key terms’, like DACA, TPS, undocumented, Dreamer. I can’t define a term that was imposed on me. It’s hard to describe something that you literally do not have the option of commenting on. It’s a weird position to be in. I realized recently that I don’t want to keep carrying that burden. I don’t want to be the face of something that is out of my control. So many years of the same thing, and thinking about your legal status every single day—at some point, you just hit a dead end, and it’s like—I don’t want to talk about it anymore. I just want to focus on me.

They don’t want to admit it, but my parents, I think, are proud. When I show them a clip of me on the news at a protest, or when they see the little articles that pop up around Oglethorpe of what I’ve been doing—secretly, I think they enjoy it. Because it’s like, whoa, she did something—she’s not letting her legal status hold her back. For them, growing up, I don’t think they ever heard ‘I love you’. Mexico is a completely different place.

My dad wanted to pursue high school, and higher education, and I can tell—that man is super smart. And I feel bad that he wasn’t able to pursue the same things that I can now. And he’s not a man of many words. He’s a very quiet man. But from the stories I’ve heard, he was smart—he just wasn’t able to pursue the same things. He was the oldest brother of the household, and a man. He had to take care of everyone else.

As for my mom—my grandpa is very machista. I don’t think I can come to a good definition, but in Mexico, this kind of male-dominated culture dictates a lot of women’s lives. Especially if you’re the daughter of a machista man. It really does make me think about my age, and what I’ve done, and their age, and what they wanted to get done—there’s parallels there. Even when I completed kindergarten was a huge deal; I went into school not knowing English and had to attend after school tutoring. I went through a lot of language and identity changes, but I made it. And I think that’s why—again, secretly—they’re proud.